A Lobbying Free-for-All

Thousands of Special Interests Vie for Influence on New Transportation Bill

By Matthew Lewis | September 17, 2009, 5:00 am | ShareThis | Print This

Speaking from a lofty perch not unlike the one he occupies as ranking Republican on the House Transportation Committee, Florida Representative John Mica looked out upon a sea of familiar faces last month at a suburban Dallas hotel. Mica was addressing the 12th Annual Transportation and Infrastructure Summit.

The conference drew more than 1,100 participants, including many veterans of transportation lobbying wars past and present. Among them: the CEOs of three of America’s freight railroad giants, directors of some of the West’s largest transit agencies, and representatives from engineering giants like Kansas City-based HNTB.

“I’ve had a chance to hear from some of you,” Mica told the luncheon crowd of transportation pros as they picked at a dessert of tiramisu, “but not all of you. … I need your ideas.”

“We don’t know if we can succeed,” he went on. “We know we can’t succeed without you getting involved.”

And with that the legislator pointed a finger back at the transportation lobby — a lobby that spent at least $45 million in Washington in the first half of this year, mostly to “help” Congress craft a new transportation bill. That lobby is composed of almost 1,800 entities of all stripes, and they are employing at least 2,100 lobbyists with intimate knowledge of transportation politics to make their cases.

Over the past two decades, this is the way federal transportation policy has largely been made in America — by a quasi-private club of interest groups and local governments carving out something for everyone, creating a nationwide patchwork of funded bypasses, interchanges, bridges, and rail lines with no overarching philosophy behind it. “Applying patches to our surface transportation system is no longer acceptable,” Congress was told in January 2008 by a bipartisan commission lawmakers themselves had created. That commission described Washington’s present policy as “pursuing no discernible national interests other than … political imperatives.”

Now, as this year’s version of the transportation debate reaches a crescendo, all of those interests are back at the table, some of them waxing eloquently about the need for reform. And some emboldened outsiders are trying to change the game, struggling to change the debate so that this year’s bill will really be different.

But don’t bet on it.

Crafting a New Bill as the Clock Ticks

U.S. Transportation Secretary Ray LaHood, foreground, applauds the billions spent on transportation projects through the stimulus bill, but critics say the lack of a long-term transportation bill could undermine those investments.For all the players in the transportation debate, the future should be, well, now. Or in a couple weeks, to be more specific. For when the current transportation law either expires on October 1 or gets briefly extended by Congress, everyone involved will begin to feel the pinch. The federal transportation system is essentially both broke and broken, out of money and in desperate need of coherent national vision. Both Congress and the transportation lobby knew crunch time was coming, and now it’s here.

U.S. Transportation Secretary Ray LaHood, foreground, applauds the billions spent on transportation projects through the stimulus bill, but critics say the lack of a long-term transportation bill could undermine those investments.For all the players in the transportation debate, the future should be, well, now. Or in a couple weeks, to be more specific. For when the current transportation law either expires on October 1 or gets briefly extended by Congress, everyone involved will begin to feel the pinch. The federal transportation system is essentially both broke and broken, out of money and in desperate need of coherent national vision. Both Congress and the transportation lobby knew crunch time was coming, and now it’s here.

By law and tradition, every few years — but rarely on schedule — Congress passes and the president signs a transportation bill that authorizes hundreds of billions in spending. That money either gets funneled back to state transportation departments and metro areas; gets earmarked for specific priority projects around the nation, or is handed over to the U.S. Department of Transportation. Individual projects, from bridge replacements and highway construction to bike lanes and bus purchases, get funded through this bill. The issue doesn’t get the attention of, say, health care, but it pretty much affects every American who leaves the house and goes anywhere. Most directly, however, it affects the public institutions that manage the nation’s transportation network, the private firms that build it, their unions, and the real estate development, manufacturing, retail, and freight-hauling industries that alter their behavior based on the network.

And therein lies the rub, in terms of crafting policy. These groups, not surprisingly, are the ones spending money to shape a new bill in their favor. And much of the lobbying power is set up to favor the way things have always been done. That usually means roads over other types of transportation. And it usually means a bit more money for everyone. But more importantly, it means picking winner projects here, there, and everywhere rather than setting over-arching goals and demanding efficient outcomes. The roster of special interests paying lobbyists in 2009 to influence either the law itself or the annual appropriations decisions that are made based on the bill’s framework is indeed formidable. Among them:

- More than 475 U.S. cities and 160 counties in 44 states, the vast majority of which are seeking funds for specific projects that will be chosen by Congress;

- More than 55 local development authorities nationwide;

- At least 65 private real estate development companies;

- At least 95 transit agencies, 25 metro and regional planning organizations, a dozen individual states, and the national lobbying associations for all three groups;

- More than 75 road and auto organizations, from highway builders and car manufacturers to interstate coalitions and trucking interests;

- At least 65 construction and engineering groups, from cement and steel makers to domestic and foreign-owned builders;

- More than 45 rail organizations, 50 shipping companies and ports, and 45 additional transportation-centric outfits, from bicycle coalitions to research groups;

- More than 140 universities seeking funds for local projects or campus research centers.

Based on disclosure data, the Center estimates that lobbying expenditures on the new surface transportation measure and associated appropriations bills exceeded $45 million for the first half of 2009 — a spending pace on a par with lobbying over climate change. Hundreds of public and private groups spent more than $19 million on lobbying teams focused solely on surface transportation, but that drastically understates the total amounts being spent by local governments, businesses, and other interest groups around the nation. Most transportation lobbyists also work on other issues for their clients, and are not required to report how much they are spending on each specific issue. But even if just 10 percent of their time was spent on transportation in the first half of 2009, that would add more than $26 million to the total spent on transportation lobbying, pushing the total past $45 million.

Traditionally, when transportation bills were debated, all these interests got along pretty well. A pair of political scientists who examined the aftermath of a similar transportation lobbying effort a decade ago found both public and private interests “were able to downplay disagreements” over which projects received more money and who spent the dollars “because everyone’s financial needs were satisfied by the monetary size” of the bill. Back then it was $218 billion. Then it reached $286 billion in 2005. The magic number being talked about now? $500 billion.

Desperate Search for New Money

Today, however, a special urgency will make a kick-the-can approach tougher than before, because the pot of money that funds these bills has run dry. And that has the lawmakers and the lobbyists in a panic, say longtime observers. Transportation bills are largely paid for through the highway trust fund, a decades-old revenue raiser that relies predominantly on the federal gas tax. Congress has left that tax rate untouched since 1993. So when the trust fund reached empty, it forced the government to transfer $8 billion from the Treasury last September just to keep the current spending stream going. It needed another $7 billion this July. The funding crisis has forced the transportation lobby to take a long look in the mirror. “The minute the spigot gets turned off you’ve got a lot of problems,” said former Transportation Department official Stephen Van Beek, who now directs the Eno Transportation Foundation, a nonprofit transportation research group.

Rep. James Oberstar’s proposed six-year, $500 billion Surface Transportation Authorization Act would spend $50 billion on a national high-speed rail system, similar to those in Europe. (Image courtesy of Sebastian Terfloth/Published under Creative Commons)Yet the House Transportation Committee, led by powerful chairman James Oberstar, a Minnesota Democrat, proposes spending $500 billion on a brand new, six-year bill. Everybody from progressives to builders supports the higher number, given the need for new roads, new bridges, new rail lines, and new jobs. But the Senate and the Obama Administration are balking, cowed by the imperative of finding new revenue — which would likely mean more taxes. Even maintaining current spending levels through 2018 would require $100 billion more than the trust fund can take in, according to the Congressional Budget Office. Finding new money would require picking from a host of politically risky options. In the short term though, the conversation usually circles back to raising the price at the pump. “We should have indexed [the gas tax for inflation] a long time ago,” Oberstar said at a hearing in July. But doing that in the midst of a severe recession seems more than a bit unlikely.

Rep. James Oberstar’s proposed six-year, $500 billion Surface Transportation Authorization Act would spend $50 billion on a national high-speed rail system, similar to those in Europe. (Image courtesy of Sebastian Terfloth/Published under Creative Commons)Yet the House Transportation Committee, led by powerful chairman James Oberstar, a Minnesota Democrat, proposes spending $500 billion on a brand new, six-year bill. Everybody from progressives to builders supports the higher number, given the need for new roads, new bridges, new rail lines, and new jobs. But the Senate and the Obama Administration are balking, cowed by the imperative of finding new revenue — which would likely mean more taxes. Even maintaining current spending levels through 2018 would require $100 billion more than the trust fund can take in, according to the Congressional Budget Office. Finding new money would require picking from a host of politically risky options. In the short term though, the conversation usually circles back to raising the price at the pump. “We should have indexed [the gas tax for inflation] a long time ago,” Oberstar said at a hearing in July. But doing that in the midst of a severe recession seems more than a bit unlikely.

Special Interests, Not National Interests

For the moment, everyone’s talking a good game about new ways of doing business. “The good news is that the financial part of the system is so broken that marginal change probably isn’t going to get the job done,” said Van Beek.

Beneath that consensus, however, lies trouble. Once hard decisions are made about which projects are funded, and which aren’t, and which funding mechanisms make sense, and which don’t, things are likely to get ugly. The reason: transportation policy and transportation bills provide depressingly stark proof that all politics is local. Each city, state, and more specifically, congressional district, has its own battles to fight.

“The system we have now is not one of national needs,” said Roy Kienitz, undersecretary for policy at the U.S. Department of Transportation, “but one that responds to local and regional decree.”

There are a couple of key issues here, say experts. The vast majority of federal transportation dollars get divided among states and localities to spend as they see fit. Congress has created dozens of programs through which those dollars flow from Washington. But there’s no overarching national strategy. And few goals. Beyond that, though, a portion of the pot is doled out project-by-project in Washington. So lots of groups end up hiring lobbyists to bypass local and state decision-makers and get projects funded federally. “High-priority projects,” the most visible of earmarks, accounted for $13.5 billion in the last bill, almost five percent. But that doesn’t include earmarking within the bill’s other narrow programs.

“The decision making process for transportation is like a piece of Swiss cheese,” said Anne Canby, director of the Surface Transportation Policy Partnership, a reform-minded advocacy group. “If you don’t get what you want, you go some place else.”

“All it is about is how much money everybody gets,” Canby said.

The $286 billion transportation bill passed in 2005 authorized 6,371 high-priority projects — nearly quadrupling the number contained in the previous measure. The so-called “Bridge to Nowhere,” a project linking Ketchikan, Alaska, to nearby Gravina Island, was one of these high-priority items included in 2005, for $223 million. Another Alaskan bridge, the Knik Arm, received four earmarks of its own totaling more than $229 million.

That process has become a runaway train of expectations and perceived entitlements, experts say, as lobbyists go hat in hand to individual members of Congress, assuming that the member will have little or no trouble delivering on the desired project. “The expectations are so high, that an individual member can deliver these projects,” said one Democratic Senate staffer familiar with transportation policy.

Congress doesn’t seem in any hurry to give up its prerogatives, however. Rather than pick no projects, they propose to simply pick them better. Critics argue the process needs to be depoliticized entirely. “Instead of going through the earmark process,” former Republican Senator Slade Gorton wrote last month in an op-ed, “projects should be funded based on merit … as components of a larger program of metropolitan investment.”

Lobbyists and their Ties to Lawmakers

Until that actually happens, though — and many wonder if it ever will — hundreds of individual actors will continue their pursuit for dollars by hiring many of Gorton’s lobbying peers, including members of the firm, K&L Gates, that now employs him.

The current battle over a new transportation bill has attracted dozens of lobbyists who have been through these fights before — often on the other side of the table.

Like Sante Esposito, a former counsel to the House Transportation Committee for 18 years, including 11 as chief Democratic counsel. Esposito’s current employer, the lobbying firm Federal Advocates, describes him in its literature as “central to the development of the current Highway Trust Fund program structure.” His daughter, Jennifer Esposito, now serves as majority staff director on the panel’s railroads subcommittee. “After leaving the Hill,” Esposito’s lobby bio continues, he “secured over $850 million for clients in [the 2005 transportation bill].” Earmarks his California clients received included $100 million for the Gerald Desmond Bridge in Long Beach. Esposito’s clients in the current fight include five California cities, an engineering firm, and the American Association of Railroads.

Broadly speaking, the transportation lobby can be divided into two categories. Some are focused on a specific area of the country or type of project. The Delaware River Port Authority, for instance, contracts with a former member of the House Transportation Committee, Democrat Robert Borski of Pennsylvania. Similarly, a pair of central Florida counties looking for road improvements hired former congressman L.A. “Skip” Bafalis, a Florida Republican. Bafalis’ 20 clients include three local governments within Mica’s congressional district.

Others with Hill experience on previous transportation bills focus on broader issues for big national clients. Like Kathy Ruffalo-Farnsworth, a former Democratic staffer with the Senate Environment and Public Works committee. She represents both the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials and the American Public Transportation Association, among others. Ruffalo-Farnsworth also served on a congressionally-chartered commission charged with recommending new policy and financing solutions.

Jack Schenendorf, former Republican chief of staff of the Transportation Committee, also lobbies for the state highway officials, as well as the Associated General Contractors of America, and others. He, too, served on a congressionally-chartered policy commission — a different one than Ruffalo-Farnsworth.

Among the other lobbyists working to influence the shape of the new bill are:

- At least two dozen individuals with experience as either House Transportation Committee staff or as personal staff to Transportation Committee members;

- More than a dozen individuals with experience on one of the three Senate committees working on transportation policy or as personal staff to committee members;

- At least three dozen former House and Senate staffers with experience working on appropriations committees or as aides for members who served on those committees;

- Former presidential appointees to various positions in the Department of Transportation, including former Secretary James Burnley;

- At least 20 former members of Congress, including one-time House Transportation Committee members Borski, William Lipinski, and Bill Brewster.

A Bias Toward Roads

Perhaps it’s no surprise that a transportation system created in the interstate highway era would tilt toward new road capacity. Few deny it works that way. The traditional breakdown in recent bills gives about 80 percent to highways and 20 percent to mass transit. What the transportation lobby argues over is how much highway expansion should continue to accelerate, as opposed to alternatives, especially in an era of concerns over energy efficiency. Activist groups tend to focus on reducing carbon use by expanding mass transit and improving the public’s access to existing roads. The trucking industry, for one, counters that gas tax fees already subsidize other travel modes too much by using money collected on roads for projects like rail lines and bike paths.

But some of those arguing historically have more clout than others. For instance, the leading voice in Washington for “aggressively” growing investment, the American Road and Transportation Builders Association, enjoys a 107-year history and has long been part of the transportation revolving door.

The Builders Association’s current in-house lobbyists include former staff from both chambers of Congress as well as a former White House liaison to the Transportation Department. The group spent more than $210,000 in the first half of this year on federal lobbying, but that number understates its impact. For instance, three association members alone — Oldcastle Materials, Vulcan Materials, and HNTB — have spent $720,000 of their own money on lobbying in 2009. Among them the three companies contracted more than a half-dozen former congressional aides to argue their cases.

In addition to leading its own grassroots member campaign and consulting other groups like the American Highway Users Alliance, the Builders Association also co-chairs the powerful Transportation Construction Coalition. “There’s not a lot of other industry coalitions I know of where you’ve got industry and labor arm-in-arm,” says Builders Association public affairs director Jeff Solsby. The coalition’s 27 members include at least 16 organizations lobbying independently on transportation this year. Together they have spent more than $2.7 million and employed at least 50 lobbyists.

The Builders Association is also one of 11 groups on the management committee of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce-led Americans for Transportation Mobility, a group that also includes the American Public Transportation Association, as well as nine Transportation Construction Coalition members. “The road builders a long time ago made a great alliance with the Chamber,” said Martin Whitmer, a founding partner of his own lobbying firm, with a long transportation background. The U.S. Chamber spent a total of $17.4 million lobbying in the first half of 2009, with some fraction of that focused on transportation issues.

Many groups within these coalitions also provide substantial campaign cash to members of Congress both through individual donations and political action committees. The Builders Association political action committee, which every congressional cycle raises thousands from top executives at member companies, including DAB Constructors, Caterpillar, and Aldridge Electric, spent $482,364 on federal candidates since 2005 according to the Center for Responsive Politics. The PAC has tended to give more to whichever party is in power, and in the last cycle gave at least $5,000 each to the top two members of both the House Transportation and Senate Environment and Public Works Committees, including $6,000 to Oberstar’s leadership PAC.

Other PACs within the construction coalition tend to cancel each other out, with many private groups swaying heavily toward Republicans and labor giving predominately to Democrats. The Associated General Contractors of America, also co-chair of the construction coalition, has given more than $1.9 million through its PAC to federal candidates since 2005. Nearly 80 percent went to Republicans, including Oklahoma Senator James Inhofe. But Democrats Oberstar and Senate Finance chair Max Baucus of Montana also received at least $9,000 during the 2008 cycle. Individual companies like engineering firms HNTB and URS also give substantial amounts on their own. The two companies’ PACs and employees provided $42,450 to Oberstar and his leadership committee during his 2008 campaign.

The Operating Engineers union, also part of the coalition, gave more money to candidates than any other building union since 2005. Of more than $6.3 million its PAC spent on Congress since 2005, more than 80 percent went to Democrats, including $30,000 to Oregon’s Peter DeFazio, the chairman of the House Transportation Subcommittee on Highways and Transit.

The American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials represents another entrenched interest long focused on roads. The association pays only a few experienced out-of-house lobbyists like Ruffalo-Farnsworth and Schenendorf, but the self-described “voice of transportation” plays a significant role in calling for spending increases.

These groups don’t work against funding for mass transit or alternative transportation projects like bicycle lanes; rather they push a ‘more money for everyone’ philosophy. Both the Builders Association and state transportation departments explicitly call for increases in mass transit spending. At the end of the day, though, their main priority is to get Congress to send more money their way.

A New Group of Players

The road lobby has not gone unchallenged, however. Rail advocates have their own coalitions — most recently OneRail, which includes six organizations with an impressive array of 55 lobbyists on the payroll. And recently, several activist groups have also increased their influence — focusing on fixing America’s infrastructure first before adding capacity, reducing transportation’s impact on the climate, and improving the public’s access to travel options. Leading the charge is Transportation for America, or T4America, the self-described “outsider public-interest coalition.” T4America represents more than 90 national and 225 state and local groups, and traces its lineage to groups that won reforms in the 1991 bill. T4America’s national grassroots campaign and Washington presence is “not to be underestimated” says one lobbyist who does not see eye-to-eye with the group.

In addition to its own lobbyists, T4America’s members include 21 organizations paying 45 lobbyists, including the National Association of Realtors and AARP, which together have spent $18.9 million lobbying Congress this year on everything from health care reform to homeowner tax credits. T4America also works closely with groups like the Urban Land Institute, Smart Growth America, and Building America’s Future. The Rockefeller Foundation funds some of these groups’ operations, and has also provided support to the Center for Public Integrity for this story and others in a series on the transport lobby. Most of the foundation’s advocacy grantees work to influence policy either through the grassroots or at the Washington level through studies and public forums. However, a handful of the grantees also spend tens of thousands lobbying for transportation policy to do things like serve low-income communities better or provide more public transportation.

Rep. James Oberstar (D-Minn.)

Rep. James Oberstar (D-Minn.)

Rep. John Mica (R-Fla.)Groups such as private railroad giants and the National Association of Realtors, which sometimes share goals with T4America members, give candidates millions of dollars per year through their political action committees. But the organizations more focused on policy reforms and increased public transit usage tend to give less, with the exception of a pair of unions within T4America’s coalition, the Transport Workers Union and the Amalgamated Transit Union. According to the Center for Responsive Politics, the two labor groups lavished more than $3.5 million on federal candidates since 2005, overwhelmingly on Democrats. While the Transport Workers Union tends to give more to incoming members of Congress, the Amalgamated Transit Union gave more to key leaders like DeFazio, House Appropriations Chairman Dave Obey of Wisconsin, and House speaker Nancy Pelosi of California. The PAC for law and lobby firm Holland & Knight, also a part of T4America, spent $17,000 on House Transportation leaders Oberstar and Mica during the same period.

Rep. John Mica (R-Fla.)Groups such as private railroad giants and the National Association of Realtors, which sometimes share goals with T4America members, give candidates millions of dollars per year through their political action committees. But the organizations more focused on policy reforms and increased public transit usage tend to give less, with the exception of a pair of unions within T4America’s coalition, the Transport Workers Union and the Amalgamated Transit Union. According to the Center for Responsive Politics, the two labor groups lavished more than $3.5 million on federal candidates since 2005, overwhelmingly on Democrats. While the Transport Workers Union tends to give more to incoming members of Congress, the Amalgamated Transit Union gave more to key leaders like DeFazio, House Appropriations Chairman Dave Obey of Wisconsin, and House speaker Nancy Pelosi of California. The PAC for law and lobby firm Holland & Knight, also a part of T4America, spent $17,000 on House Transportation leaders Oberstar and Mica during the same period.

Many of these groups — along with, environmentalists awakened by the climate fight — are having an impact, observers say. The groups are also unified by support of a proposed National Transportation Objectives Act introduced by Democratic House members in June, as well as an outline by senior Democrats on the Senate Commerce Committee called the Federal Surface Transportation Policy and Planning Act. Both measures set specific benchmarks for federal transportation policy: reducing the number of vehicle miles traveled, increasing freight rail capacity, and bringing transportation-related CO2 emissions down by 40 percent over the next two decades.

What Happens Next

For the time being, most of the transportation lobby is expressing cautious support for Oberstar’s six-year, $500 billion Surface Transportation Authorization Act, which was marked up by the Highways and Transit Subcommittee but has yet to come to a full committee vote. That bill — considered drastic reform by many — promises to consolidate or terminate more than 75 programs, create a national strategic plan, and make state and local governments plan for “specific goals.” The bill also moves toward a national freight plan, and creates a $50 billion funding stream for high speed rail, while promising policy beyond just more roads. It is clear that a host of disparate lobbying groups have had input, although no one has yet decided how to pay for it all. That call is up to the House Ways and Means Committee, which has yet to commit to any specific solution.

Meanwhile, the Senate and the White House have other plans. The reluctance to engage in a debate that likely ends in new taxes prompted Transportation Secretary Ray LaHood to suggest an 18-month extension of present law, just one day before Oberstar publicly released his bill on June 18. Mica called the extension proposal a “betrayal,” and Oberstar has continued to push his bill. But the Senate followed the administration’s advice, passing portions of an extension out of three separate committees. To keep the trust fund solvent until 2011, Senate Democrats suggest reimbursing it $26.8 billion. But that would come from the general treasury, meaning Congress either needs to find an offset or chalk it up to the national debt.

House leaders proposed some nontraditional ways to collect more money, such as a tax on oil speculators, a national sales tax, or the use of more tolling and private partnerships. A “miles traveled” tax, which levies specific charges on drivers based in part on the number of miles they drive, has gained the support of Congress’ two national policy commissions, but that option would require years to implement and would likely be a tough sell to the public.

That leaves the gas tax. All the big players in the transportation lobby accept the idea of an increase and are offering Congress their support. This includes the truckers, road builders, and even the U.S. Chamber of Commerce. But even Oberstar said during congressional testimony that the gas tax will not be raised during a recession, and no one in Congress is stepping up to argue the case.

Until the funding question is solved, it’s not clear a bill can move forward. And even if and when it does, there’s still plenty of policy to argue about: Roads. Transit. Bridges. Funding formulas. State allocations. Projects of national significance. Earmarks. Growth policies.

“I think people agree on the problems,” said Jeffrey Boothe, a mass transit lobbyist with Holland & Knight. “But where there’s not agreement is the level of priorities. We haven’t really had those conversations.”

Now might be a good time to start. The law governing America’s transportation system expires on October 1.

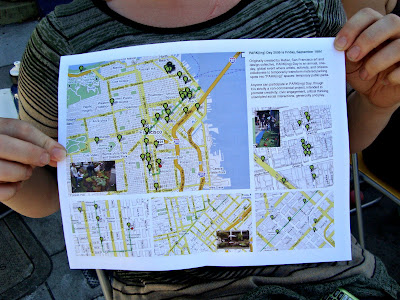

In the meantime, I'd like to see local officials beginning a conversation with state and national officials -- and getting some of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act money (H.R. 1, the stimulus package passed by Congress, and signed by President Obama, in early 2009) dedicated to preparations for peak oil and not just thrown willy nilly at "shovel ready projects" -- as appears to have happened along Geary Boulevard in San Francisco where, a few years from now, this artery is scheduled to be transformed by Bus Rapid Transit anyway.

In the meantime, I'd like to see local officials beginning a conversation with state and national officials -- and getting some of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act money (H.R. 1, the stimulus package passed by Congress, and signed by President Obama, in early 2009) dedicated to preparations for peak oil and not just thrown willy nilly at "shovel ready projects" -- as appears to have happened along Geary Boulevard in San Francisco where, a few years from now, this artery is scheduled to be transformed by Bus Rapid Transit anyway.

U.S. Transportation Secretary Ray LaHood, foreground, applauds the billions spent on transportation projects through the stimulus bill, but critics say the lack of a long-term transportation bill could undermine those investments.

U.S. Transportation Secretary Ray LaHood, foreground, applauds the billions spent on transportation projects through the stimulus bill, but critics say the lack of a long-term transportation bill could undermine those investments. Rep. James Oberstar’s proposed six-year, $500 billion Surface Transportation Authorization Act would spend $50 billion on a national high-speed rail system, similar to those in Europe. (Image courtesy of Sebastian Terfloth/Published under

Rep. James Oberstar’s proposed six-year, $500 billion Surface Transportation Authorization Act would spend $50 billion on a national high-speed rail system, similar to those in Europe. (Image courtesy of Sebastian Terfloth/Published under  Rep. James Oberstar (D-Minn.)

Rep. James Oberstar (D-Minn.) Rep. John Mica (R-Fla.)

Rep. John Mica (R-Fla.)